The LEMON LADY met a man who kindly stopped to speak with her.

He explained that he had had an Audi 5000. Remember those? 1980's? Maybe you're too young!

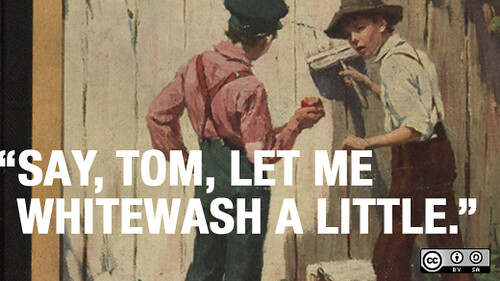

The continuing Auto Industry Whitewash remains unchanged to conceal their failures!

The list of Auto Industry Failures is lengthy, adequately documented, TOYOTA SUDDEN ACCELERATION = GET OUT OF JAIL FREE CARD!

TAKATA blasts drivers with SHRAPNEL...AND THEY KNEW!

NHTSA FLUNKIE DAVID FRIEDMAN....YADA YADA....is going to tell you DRIVER ERROR!

NOT SO!

Auto Industry: BLAME DRIVER ERROR! BLAME THE FLOOR MATS! BLAME ANYTHING EXCEPT FIX THE CRAP YOU SELL!

Text below:

Toyota in the docket: acceleration troubles have long history for automakers

A Look Back at the Audi 5000 and Unintended Acceleration

Friday, March 14th, 2014 by Michael Barr

I was in high school in the late 1980′s when NHTSA (pronounced “nit-suh”), Transport Canada, and others studied complaints of unintended acceleration in Audi 5000 vehicles. Looking back on the Audi issues, and in light of my own recent role as an expert investigating complaints of unintended acceleration in Toyota vehicles, there appears to be a fundamental contradiction between the way that Audi’s problems are remembered now and what NHTSA had to say officially at the time.

Here’s an example from a pretty typical remembrance of what happened, from a 2007 article written “in defense of Audi”:

This sequence of, first, a throttle malfunction and, then, pedal confusion was summarized in a 2012 review study by NHTSA:

It is unclear whether the “electronic control unit” mentioned by NHTSA was purely electronic or if it also had embedded software. (ECU, in modern lingo, includes firmware.) It is also unclear what percentage of the Audi 5000 unintended acceleration complaints were short-duration events vs. long-duration events. If there was software in the ECU and short-duration events were more common, well that would lead to some interesting questions. Did NHTSA and the public learn all of the right lessons from the Audi 5000 troubles?

Tags: architecture, embedded, engineering, firmware, reliability, safety

Here’s an example from a pretty typical remembrance of what happened, from a 2007 article written “in defense of Audi”:

In 1989, after three years of study[], the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) issued their report on Audi’s “sudden unintended acceleration problem.” NHTSA’s findings fully exonerated Audi… The report concluded that the Audi’s pedal placement was different enough from American cars’ normal set-up (closer to each other) to cause some drivers to mistakenly press the gas instead of the brake.And here’s what NHTSA’s official Audi 5000 report actually concluded:

Some versions of Audi idle-stabilization system were prone to defects which resulted in excessive idle speeds and brief unanticipated accelerations of up to 0.3g. These accelerations could not be the sole cause of [long-duration unintended acceleration incidents], but might have triggered some [of the long-duration incidents] by startling the driver.”Contrary to the modern article, NHTSA’s original report most certainly did not “fully exonerate” Audi. Similarly, though there were differences in pedal configuration compared to other cars, NHTSA seems to have concluded that the first thing that happened was a sudden unexpected surge of engine power that startled drivers and that the pedal misapplication sometimes followed that.

This sequence of, first, a throttle malfunction and, then, pedal confusion was summarized in a 2012 review study by NHTSA:

Once an unintended acceleration had begun, in the Audi 5000, due to a failure in the idle-stabilizer system (producing an initial acceleration of 0.3g), pedal misapplication resulting from panic, confusion, or unfamiliarity with the Audi 5000 contributed to the severity of the incident.The 1989 NHTSA report elaborates on the design of the throttle, which included an “idle-stabilization system” and documents that multiple “intermittent malfunctions of the electronic control unit were observed and recorded”. In a nutshell, the Audi 5000 had a main mechanical throttle control, wherein the gas pedal pushed and pulled on the throttle valve with a cable, as well as an electronic throttle control idle adjustment.

It is unclear whether the “electronic control unit” mentioned by NHTSA was purely electronic or if it also had embedded software. (ECU, in modern lingo, includes firmware.) It is also unclear what percentage of the Audi 5000 unintended acceleration complaints were short-duration events vs. long-duration events. If there was software in the ECU and short-duration events were more common, well that would lead to some interesting questions. Did NHTSA and the public learn all of the right lessons from the Audi 5000 troubles?

Tags: architecture, embedded, engineering, firmware, reliability, safety

One Response to “A Look Back at the Audi 5000 and Unintended Acceleration”

http://embeddedgurus.com/barr-code/2014/03/a-look-back-at-the-audi-5000-and-unintended-acceleration/

MAY 1987 - VOLUME 8 - NUMBER 5

T H E C A S E A G A I N S T C O R P O R A T E C R I M E

Audi: Shifting the Blameby Thomas Wathen

Thomas A. Wathen is Executive Director of the New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG) and has worked extensively on auto safety issues. |

The Multinational Monitor

MAY 1987 - VOLUME 8 - NUMBER 5

Audi: Shifting

the Blame

by Thomas Wathen

=====================================================

DOT-TSC-NHTSA-88-4 September, 1988

Final Report

Appendix H:

Study of Mechanical and Driver -

Related

Systems of the Audi 5000 Capable

of

Producing Uncontrolled Sudden

Acceleration

Incidents

Gary Carr

John Pollard

Don Sussman

Robert Walter

Herbert Weinstock

U.S. Department of Transportation

Research and Special Programs

Administration

Transportation Systems Center

Cambridge, MA 02142

By Raymond Paul

Johnson and Cory G. Lee

It was the perfect day

that turned into a nightmare. Bulent and Anne

Ezal were on a trip to Big Sur, traveling one of the most ruggedly

beautiful stretches of the California coastline. As lunchtime drew near, Bulent

eased the couple’s Toyota Camry into a parking

space near a coastal restaurant hugging the steep and rocky bluff overlooking

the waves.

Miraculously, Bulent suffered few permanent physical injuries. But his beloved wife Anne died a horrifying death.

This Toyota Camry went off a cliff and plunged 75 feet,

killing a passenger, and her husband at the wheel could do nothing to stop

it

The tragedy of that day has been replicated in accidents all over America, creating a tidal wave of trouble for an auto manufacturer that once commanded the pinnacle of consumer trust. Toyota has been called to task by congressional investigators, attorneys and the general public over a phenomenon that has afflicted thousands of vehicles, maimed and killed motorists, and earned its own moniker: sudden unintended acceleration.

Toyota of late has embraced explanations that challenged credulity, suggesting that unintended accelerations can be caused by “sticky gas pedals” or “all-weather floor mats” that can jam the pedal.

In the Ezals’ case, as in many other reported runaway accelerations, their Toyota did not have all-weather floor mats or the specific gas pedals identified in Toyota’s press releases. So what happened?

The most likely explanations can be discerned with a look at the past, present and future – a look back in history, an examination of pivotal issues being publicly disregarded by Toyota, and the consideration of new techniques for discovering the root cause of this deadly defect.

A brief history of uncontrolled accelerations

The syndrome now afflicting Toyotas may be news to many, but unintended accelerations are nothing new in the auto industry.

In 1978, Volkswagen began selling the first Audi 5000s in the United States. Sales were strong, with sales of the Audi flagship doubling in its first seven years in the U.S. market. But these popular vehicles had a recurring problem: uncontrolled acceleration.

From 1978 to 1987,

consumers reported more than 1,500 crashes involving sudden acceleration of Audi

5000s, with 400 reported injuries and seven fatalities. Many of the crashes were

similar: the car was idling with the automatic transmission in “park,” the

driver shifted into “drive” or “reverse,” and the car would, suddenly and

without warning, wildly accelerate. Often the Audis could not be stopped before

hitting other cars, trees, walls, or even people.

One of those killed was six-year-old Joshua Bradosky. He died when an Audi 5000, driven by his mother, surged forward, crashing him through a garage and pinning him to the garage wall.

Audi’s response was,

essentially: the car is not defective, the drivers are. Audi’s public relations

staff accused the drivers, emphasizing that “maybe people are

putting their foot on the wrong pedal.”

The response by the National

Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA): The car is not

defective; the drivers are. In 1989, NHTSA completed its investigation into

“sudden acceleration incidents” (“SAI”), concluding, “most SAI probably involve the driver

unintentionally pressing the accelerator when braking was intended.” In short,

despite the increased frequency of sudden accelerations in certain model

vehicles, and the driver (in virtually every incident) reporting “foot on the

brake” rather than the accelerator, NHTSA concluded it was all merely the result

of the driver pressing the wrong pedal.

Despite this ultimate “finding” by NHTSA, as a result of prior work by trial attorneys, journalists, safety advocates, and consumers, the Audi 5000 had been recalled several times to correct problems that NHTSA itself acknowledged could cause sudden acceleration.

In 1982, in a move shockingly similar to today’s Toyota headlines, NHTSA forced the recall of the Audi 5000 because the driver’s floor mats could cause sudden acceleration. Later, the placement of the brake pedal was blamed for some sudden accelerations, and the Audi 5000 was recalled again for repairs.

In 1987, NHTSA

identified defects that could cause “engine surge” and demanded the recall of

some Audi 5000s yet again. Finally, that same year, the Audi 5000 was recalled

to retrofit an automatic shift lock to prevent “unexpected, sudden acceleration,

without prior warning.” Audi touted this final recall as the solution to most of the sudden

accelerations incidents.

With NHTSA’s investigation into “sudden acceleration incidents” closed, and most unintended accelerations attributed to driver error, NHTSA made no further recalls of the Audi 5000. Long after the recalls, however, consumers continued to report runaway accelerations with the Audi 5000, even on vehicles that received all recall repairs.

The 1990s and Ford Motor Company

In the 1990s, consumers

began to report that automobiles with popular cruise control systems had runaway

accelerations. Ford Motor Company absorbed much of the

criticism, with numerous lawsuits filed against it as well as multiple NHTSA

recalls related to sudden acceleration.

Unlike Audi’s problem with the Audi 5000, Ford’s runaway acceleration

problems crossed into many models and various brands:

Aerostars, Contours, Escapes,

Explorers, F-Series Trucks, Focus

Hatchbacks, Tauruses, Mercury

Mystiques and Mercury Sables.Most of these Ford recalls involved the cruise control system. There was particular focus on a design that allowed contaminants into the speed control cable conduit or caused damage to the cable itself, resulting in either a wide-open throttle or surging throttle.

However, the recalls

ignored key consumer concerns regarding runaway accelerations. Prominent among

them was whether transient electromagnetic interference (EMI) could cause these

unwanted accelerations. Some experts believed that transient EMI could cause the electronic cruise control to signal

the throttle to open, despite the absence of accelerator input.

In addition, Ford was

privy to information indicating that EMI could cause vehicles to suddenly accelerate

out-of-control. Indeed, in internal investigations on sudden acceleration,

Ford concluded that sudden unintended acceleration incidents increased with the

introduction of broadly applied electronics in 1984. Ford also documented in

internal memoranda that various electromagnetic failures, including EMI, could

cause sudden unintended acceleration.

Ford apparently learned that “the vehicle speed maintenance control

system or ‘cruise control system’ . . . is capable in the event of ‘failure or

malfunction’ of opening the throttle a substantial amount without driver input.”

Indeed, former Ford employees have admitted that unwanted electrical impulses

could open the throttle, causing sudden unintended acceleration.

In one reported

incident, a Ford engineer, investigating a Ford

Expedition for cruise control problems, found that after pressing the

“resume” button, “the vehicle kept accelerating beyond the set speed and

wouldn’t respond to brakes or the off switch.” Upon examining the truck,

however, Ford could not find anything out of the ordinary.

In another reported incident, during a test drive of a

Mercury Grand Marquis, a Ford employee shifted into “drive” and

the engine raced with the wheels spinning, as if the accelerator were floored.

The employee stopped the car by braking as hard as he could. The car later

checked out normal.

In yet another reported incident, a Ford employee crashed an

experimental Aerostar prototype. After shifting into gear, the vehicle

accelerated to full throttle, tires squealing. The employee removed his foot

from all pedals, thinking he had accidentally floored the accelerator, but the

van continued to accelerate. He shifted into “park” but could not avoid crashing

into a wall.

Despite the above, Ford and virtually the entire industry continued to rebuff opinions that EMI could cause runaway accelerations, especially during related litigations.

The 2000s bring trouble for Toyota/Lexus

On August 28, 2009, with a California Highway Patrol Officer at the wheel, a passenger in a new Lexus ES 350 made a frantic call to 911. Their vehicle was out-of-control, weaving through traffic at 120 miles per hour. The passenger’s final frantic words were “we’re in trouble . . . there’s no brakes.” The driver, his wife, teenage daughter, and brother-in-law, the 911 caller, were all killed as the vehicle slammed into another car and careened down an embankment.

Since 2001, consumers

have lodged more than a thousand reports of sudden unintended acceleration in

Lexus and Toyota vehicles. NHTSA officials told a Congressional committee in

early March that the agency had received 52 complaints of fatalities involving sudden unintended

acceleration in Toyota vehicles since 2000. A Los Angeles Times

review of public records and interviews with authorities found at least 56 deaths blamed on sudden acceleration in Toyota and

Lexus vehicles. In contrast, sudden unintended acceleration in all other

vehicles made by other manufacturers resulted in only 11 deaths.

The floor mat recall, however, did not end the inquiry. NHTSA, in an unprecedented rebuke, responded to Toyota’s claim that no defects existed in their vehicles with compatible and properly secured floor mats. NHTSA publicly stated that it recognized an “underlying defect” in the design of the Toyota and Lexus accelerator pedals and the drivers’ foot wells.

In January 2010, Toyota announced yet another related recall. This one recalled millions of more vehicles to correct “sticking accelerator pedals.” Toyota’s press release stated that its continuing investigation found that certain accelerator pedals could mechanically stick in a partially depressed position, or return slowing to the idle position. Later in January, Toyota announced an unprecedented decision to halt sales and production of eight models until it could determine how to stop the gas pedals from sticking and causing unintended accelerations.

However, we believe that Toyota’s runaway acceleration problems will not end at “jamming floor mats” or “sticky gas pedals.” A telling point is that complaints of unintended acceleration in Toyota and Lexus vehicles increased dramatically after employment of electronic throttles in the last decade.

In some models, sudden acceleration complaints increased five-fold after introduction of electronic throttles.

The ignored issue and solutions

Like the proverbial “elephant in the room”, the EMI issue must be directly addressed by Toyota and the rest of the auto industry. EMI is real. The aerospace industry has been dealing with the ramifications of EMI/EMC (electromagnetic interference/electromagnetic compatibility) since the 1960s. Said simply: The more sophisticated electronics one stuffs into a small area, the more lethal the EMI/EMC issue.

We now rely on an unprecedented number of electronic gizmos in every new car–some more than others. Toyota, as the largest automobile manufacturer and an undisputed leader in electronic advances for automobiles, is at the forefront. As such, and with its current runaway acceleration woes, Toyota will have to face the issue first.

EMI/EMC

The electronic throttle system that Toyota introduced at the turn of the 21st Century replaced the mechanical link (usually a steel cable) between the driver’s foot and the engine’s acceleration with a series of sensors, microprocessors, electric motors and wiring. These devices were located among a growing number of additional sensors, processors, and wiring for a myriad of other electronic subsystems in a relatively small space in the vehicle’s engine area. This, in and of itself, is a classic recipe for EMI/EMC problems.

As the aerospace industry learned decades ago, manufacturers cannot simply continue to jam electronic devices into small areas without testing for and designing away EMI dangers. If they do, spurious signals that inadvertently and randomly excite near-by electronics are inevitable. If those near-by electronics include the engine control unit (or electronic throttle system), runaway accelerations are to be anticipated.

EMI/EMC dangers can include stray voltage, algorithm defects in the related software of the microprocessor components, and random signals that excite other subsystems (such as opening throttle control units).

Toyota, understandably, wants a “quick fix” to its runaway acceleration problems. Sales, reputation and peoples’ lives depend on it. But limiting its investigations to mechanical things such as “jamming floor mats” and “sticky gas pedals” is a tragic mistake. Toyota (and the industry as a whole) can no longer afford to disregard “the elephant in the room”: EMI/EMC.

The solution is not a “quick fix.” Eliminating EMI/EMC dangers is a system design and test issue that affects every electronic component and computer-driven subsystem in the vehicle. And the more electronic components and microprocessors in a vehicle, the deeper and darker the problem.

Besides testing for EMI/EMC dangers at each step of the design process, safety analyses must be done. In particular, Failure Modes and Effects Analyses (FMEA) must be conducted to show that the system-design is free of EMI dangers. Through careful design, testing and on-going FMEA, electronic devices can be safely integrated, insulated and, if need be, isolated, and all associated algorithms can be verified and validated to virtually eliminate the risk of EMI. In more than 25 years of product liability litigation, however, we have yet to see an FMEA from any auto manufacturer that comes remotely close to accomplishing and documenting the above.

Now is the time. Toyota, as industry leader and saddled with its current “runaway acceleration” problems, should lead the way. Future designs must thoroughly address EMI/EMC from the ground up. Lives depend on it.

But what about the Toyota vehicles already on the road? Retrofit and perhaps redesign is necessary.

If Toyota has not already done so internally, it should immediately amass what the aerospace industry calls a “tiger team” of knowledgeable engineers across multiple disciplines (including auto design, electronics, software and safety engineers) to beat back its deadly problems. Suspect components and software should be modified. Susceptible electronic devices, including wiring and sensitive components, should be shielded, insulated and if necessary isolated or retrofitted to eliminate EMI dangers.

The role of product liability litigation

For well over 30 years, product liability litigation has been at the forefront of auto safety. Think Pinto “exploding gas tanks,” interior padding, airbag safety, roll-over propensity, etc. Litigation is especially effective where industry progress is thwarted by profit concerns and federal regulation is dwarfed by politics.

Even with today’s government and media interest in sudden unintended acceleration, troubles loom and questions remain unanswered. Toyota’s inconsistent mechanical “explanations,” the fact that the issue isn’t isolated to just one manufacturer, the reality of EMI/EMC dangers and the essential disregard of those threats by manufacturers and government watchdogs leave the public at risk. As with so many previous automotive defects, that safety void will exist until manufacturers are spurred to find the real solution. And, as in the past, that void will be filled by product liability litigation, and the type of knowledge and techniques that effective lawyers can use for the good of consumers across the nation.

Raymond Paul Johnson is a Los Angeles product safety attorney who holds a masters degree in engineering, and has been prosecuting defective acceleration cases since the 1980s. He is co-author of the national treatise “Defective Product: Evidence to Verdict,” a long-time member of Consumer Attorneys of California, and a Governor-Emeritus of the Consumer Attorneys Association of Los Angeles.

Cory G. Lee is an attorney with Raymond Paul

Johnson, A Law Corporation. He is a member of Consumer Attorneys of

California and the Consumer Attorneys Association of Los Angeles, and practices

in the areas of products liability, hazardous roads, business law and other

civil litigation matters. He and Raymond Paul Johnson are representing the

Ezals against Toyota.

JUST MY OPINION....AT THE MOMENT!